Vitamin D (also known as “calciferol”) is a fat-soluble vitamin that can be found naturally in a few foods, added to others, or purchased as a dietary supplement. When ultraviolet (UV) rays from sunshine strike the skin and activate vitamin D production, it is also created endogenously.

Vitamin D acquired from the sun, meals, and supplements is physiologically inactive and must be activated in the body by two hydroxylations. Vitamin D is converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], commonly known as “calcidiol,” by the first hydroxylation, which takes place in the liver. The physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], also known as “calcitriol,” is formed by the second hydroxylation, which occurs largely in the kidney[1].

Vitamin D aids calcium absorption in the gut and keeps serum calcium and phosphate levels in check, allowing for normal bone mineralization and preventing hypocalcemic tetany (involuntary contraction of muscles, leading to cramps and spasms). It’s also required for osteoblasts and osteoclasts to develop and repair bone [1-3]. Bones can become thin, brittle, and deformed if they don’t get enough vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency protects toddlers from rickets and adults from osteomalacia. Vitamin D, in conjunction with calcium, aids in the prevention of osteoporosis in the elderly.

Other functions of vitamin D in the body include inflammation reduction and control of cell proliferation, neuromuscular and immunological function, and glucose metabolism [1-3]. Vitamin D influences the expression of several genes that code for proteins that control cell proliferation, differentiation, and death. Vitamin D receptors can be found in many tissues, and some of them convert 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D.

Vitamin D comes in two primary forms in foods and dietary supplements: D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol), which differ chemically solely in their side-chain configurations. In the small intestine, both types are efficiently absorbed. Simple passive diffusion and a mechanism involving intestinal membrane carrier proteins are involved in absorption [4]. Vitamin D absorption is aided by the presence of fat in the gut, however some vitamin D is absorbed even without it. Vitamin D absorption from the stomach is unaffected by age or fat [4].

Vitamin D status is now determined by the concentration of 25(OH)D in the blood. It accounts for vitamin D produced naturally as well as vitamin D received from foods and supplementation [1]. 25(OH)D has a rather long circulation half-life of 15 days in serum [1]. The amount of 25(OH)D in the blood is measured in nanomoles per litre (nmol/L) and nanograms per millilitre (ng/mL). 1 ng/mL is equal to 2.5 nmol/L, while 1 nmol/L is equal to 0.4 ng/mL.

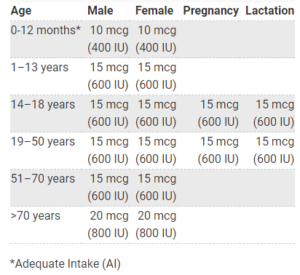

Recommended Intakes for Vitamin D

Sources of Vitamin D

Food

Few foods naturally contain vitamin D. The flesh of fatty fish (such as trout, salmon, tuna, and mackerel) and fish liver oils are among the best sources [1]. An animal’s diet affects the amount of vitamin D in its tissues. Beef liver, egg yolks, and cheese have small amounts of vitamin D, primarily in the form of vitamin D3 and its metabolite 25(OH)D3.

Common sources of that are high in vitamin D are:

- Salmon, herring, tuna and sardines, the fatty fishes

- Egg yolks! (eating whole eggs is more beneficial than you know)

- Mushrooms

- Soy milk

- Cheese

- Beef liver

- Orange

- Fortified yogurt and milk

- Cod liver oil/Fish oil

Sun exposure

Most people in the world meet at least some of their vitamin D needs through exposure to sunlight [1]. Type B UV (UVB) radiation with a wavelength of approximately 290–320 nanometers penetrates uncovered skin and converts cutaneous 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which in turn becomes vitamin D3. Season, time of day, length of day, cloud cover, smog, skin melanin content, and sunscreen are among the factors that affect UV radiation exposure and vitamin D synthesis. Older people and people with dark skin are less able to produce vitamin D from sunlight [1]. UVB radiation does not penetrate glass, so exposure to sunshine indoors through a window does not produce vitamin D

References

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2010.

- Norman AW, Henry HH. Vitamin D. In: Erdman JW, Macdonald IA, Zeisel SH, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition, 10th ed. Washington DC: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Jones G. Vitamin D. In: Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler TR, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014.

- Silva MC, Furlanetto TW. Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: A systematic review. Nutr Rev 2018;76:60-76. [PubMed abstract]

- Sempos CT, Heijboer AC, Bikle DD, Bollerslev J, Bouillon R, Brannon PM, et al. Vitamin D assays and the definition of hypovitaminosis D. Results from the First International Conference on Controversies in Vitamin D. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:2194-207. [PubMed abstract]

Read about the Premenstrual Syndrome by the author here

Author

#fittrcoach

Sreejata Mukherjee

Certified Fitness & Nutrition Consultant

A media personnel turned a fitness enthusiast and then a coach.